Welcome to Sahel Dispatch’s Southwest Mali Security Newsletter for May 2023. This month we dig into the jihadist incidents in southwest Mali—Kayes, Koulikoro, and Sikasso regions—during May. We focus on southwest Mali because it is home to rich mineral deposits and several industrial mines, which generate the bulk of Mali’s revenue. It also borders Senegal, Guinea, and Côte d’Ivoire, home to population centers and extensive commerce, business, and investment.

Jihadists begin shifting to the southwest

So far, the southwest has experienced less jihadist activity than in central and northern Mali. This is beginning to change—resulting in an increased risk to Mali’s mining sector and Senegal, Guinea, and Côte d’Ivoire.

In April and May, we began seeing Katibat Macina—part of the al-Qaeda-affiliated Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM) coalition—beginning to shift some capability from central Mali to parts of Kayes and Koulikoro regions, especially Kita and Kangaba cercles.

We think the jihadists’ shift to the south is a strategic move intended to regain momentum and avoid pressure from aggressive Malian Armed Forces and Wagner Group operations in central Mali. Over the past year and a half, the Malians and Russians cut Katiba Macina’s access to supplies by targeting markets and weakened its intelligence networks through arbitrary arrests. Perhaps most importantly, their violent and often indiscriminate operations killed jihadists and civilians alike. To maintain effectiveness and survive, the jihadists had to establish a presence somewhere else—southwest Mali.

So far, we’ve only seen Katiba Macina establish cells in southwest Mali, not deploy groups of active fighters. These cells activate to conduct attacks—like the four in Kayes—and then return to hiding. We don’t expect a dramatic increase in jihadist incidents in the southwest until they establish a recruiting base and deploy larger groups of fighters there. Until then, expect a gradual increase in incidents slightly affected by seasonal changes in the weather.

Incidents

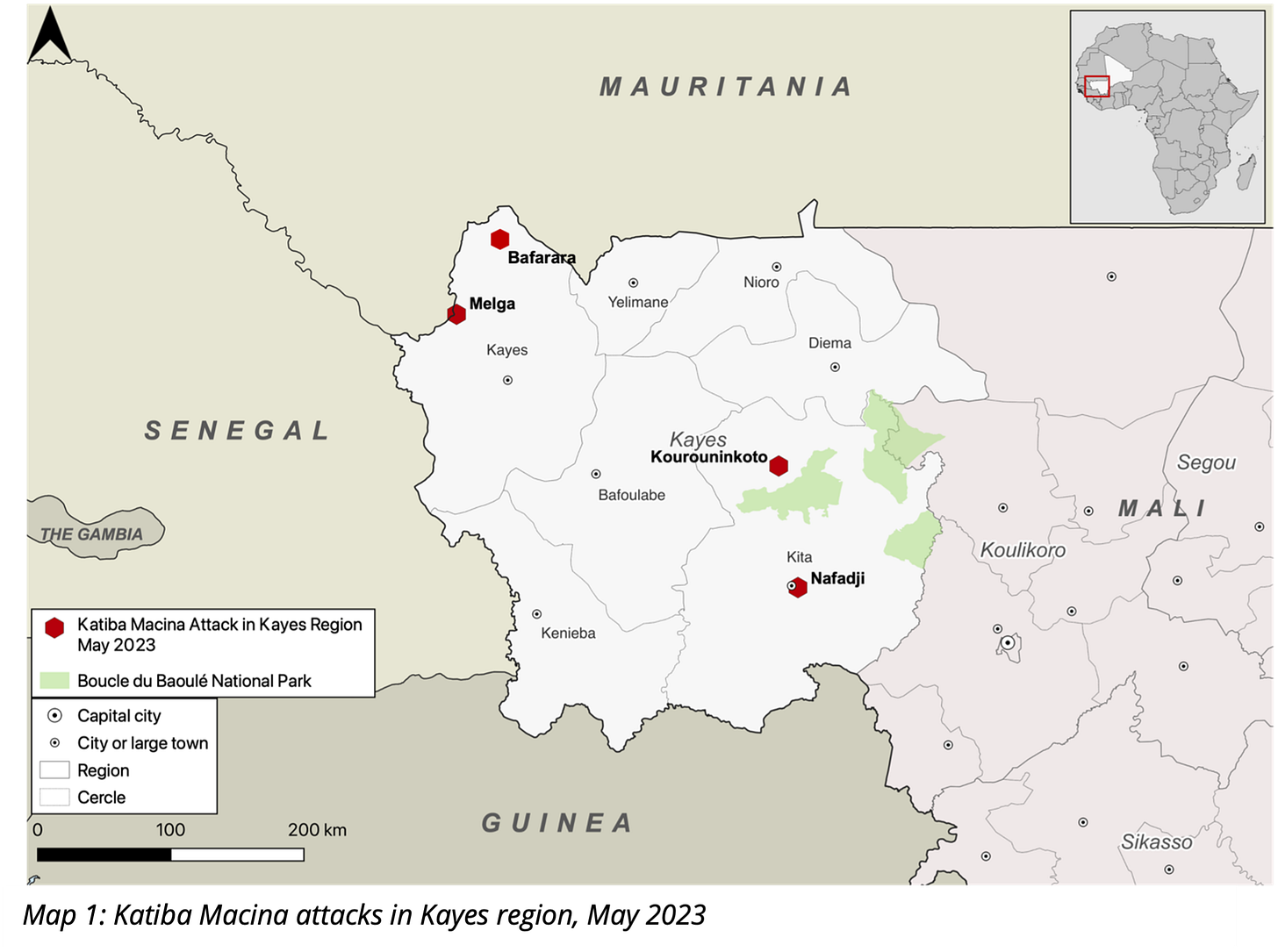

The most obvious sign of the jihadist shift was in Kayes region, where Katiba Macina carried out four attacks in the space of 12 days in May. Its targets included a military convoy (9 May, in Kourouninkoto), a border post (15 May, in Melga, variant Melgue), a security post (20 May, in Nafadji, also known as Zanakoro), and a border post (21 May, in Bafarara).

We pay close attention to Koulikoro region because it surrounds Mali’s capital city, Bamako, and stretches to the Guinea border. We think there are several jihadist cells there, including those responsible for at least two (13 January, in Ouenzindougou, and 4 February, in Narena) of the five attacks surrounding Bamako in January and February.

In May, jihadist activity in Koulikoro included the explosion of two improvised explosive devices (IED) against Malian military targets near Nara (2 May) and Goubmou (3 May), resulting in at least five deaths. There was also a kidnapping in Sebete (13 May) and an attack against a customs service post in Didieni (18 May). In response, Malian security and defense forces conducted at least one operation against jihadists, resulting in at least one arrest.

In Sikasso region, in May, we saw jihadists establish a checkpoint (16 May, in Boura), kidnap someone, and intimidate civilians. This is the fewest jihadist incidents we’ve seen in almost a year, even though Sikasso typically experiences more. Most have occurred in the northern Sikasso region near Segou and Burkina Faso and reflect the conflict in those areas, not Katiba Macina’s southwestern shift.

The bottom line

Al-Qaeda-affiliated Katiba Macina’s shift south does not only mean greater threat levels for Mali’s capital and critical travel routes. It also suggests that the Malian government's assurances of progress—which seem to be convincing many locals—might not be telling the whole story.

Military operations have weakened the jihadists in central Mali, but the effect is something akin to squeezing a balloon in one location, which pushes air to other parts of the balloon. Now they’ve begun shifting to the southwest, bringing the threat of violence closer to the capital, Senegal, and Guinea. We also must not forget that Ménaka region in northeastern Mali has, for all intents and purposes, fallen to the Islamic State. This reflects Mali’s weakness—it can only concentrate its efforts in one region.

We think there is a growing risk that jihadist activity will eventually spill over into neighboring countries, especially Senegal and Guinea—which face immediate and long-term threats. The immediate threat is the sheer proximity of jihadists to both countries. In addition, instability in Mali may lead to population displacements, with refugees fleeing to neighboring countries.

The long-term threat to neighboring countries could stem from a situation in which Mali completely loses control over the situation, undermining the country’s very viability. To be blunt, Mali does not have a handle on its jihadist problem. The worse it gets, the greater the chance that Senegal, Guinea, and Côte d’Ivoire will find themselves in a regional quagmire.

14 North helps businesses and organizations succeed in Sub-Saharan Africa’s emerging and frontier marketspaces by delivering insights that increase opportunity and minimize risk. To learn more, please get in touch with us at info@14nstrategies.com or www.14nstrategies.com.